Early Life

When D'Arcy Niland died suddenly in 1967, it seemed not so much that he'd left this life, but that he'd rushed off to another, full of optimism and good humour, certain that there'd be a thousand more stories to find and write. For he was a great man for a walkabout and must have spent a good fifth of his life with a swag up, hitching rides, hopping freight trains, camping anywhere he could get a job or a feed. After he married, it was his custom to fire telegrams back to his home - from Port Augusta, "Missing you like billy-O" and, a day later from Pimba, "Got over it."

Very Irish in looks and temperament, he was Australian to his bones, loving not only the vast pastoral lands and the stony deserts but the little peppertree towns that were, so often, the locale of his short stories.

"I got the habit (of wandering) during the last years of the Depression, when half New South took to the roads. Dad and I joined the army of the strayed, the eccentric, and the starving."

"We dug potatoes for squatters at Guyra, Stonehenge and Llangothlin setting off in the dark over roads ironbound with frost, working in the bleak paddocks as long as light lasted. Then we'd trudge back to the shack, to cook corned beef and spuds over an open fire. Those country nights! Deathly silence broken only by a whimper from father or a whinge from son, as we blew on our chilblains, like a fistful of wasps."

His father, Frank Niland, was a woolclasser by trade, a slim man with a foxy glance and red splashes down his cheeks. He was saucy and fightable, more often out of work than in, and his family had very little but hard times. "Drunk or sober, he was a compulsive talker. If no one would listen he'd talk to himself. He'd sit there, a newspaper in his hands, crooked glasses tied on with the wire from a gingerbeer bottle, arguing with himself about the fundamentacious facts of politics."

"For, like H. G. Wells's Mr Polly, if a word was missing from the English language he richly supplied it. He was a bush lawyer, drowning squatters and union reps in floods of words, real and invented. He was known as the Professor." The Professor had many good points, and one would think it no accident that the happy-go-lucky, good hearted Larrissey, in Dead Men Running was given the Christian name of Frank. The Larrisseys, with their real family spirit, their rough, tough life uncomplainingly accepted, seem a reflection of the eternally hard-up Nilands of the little country town Glen Innes, in New South Wales.

D'Arcy Niland was never shy about his background. He said: "Why hide anything? If you've surmounted tough times, it's to your credit, anyway. You don't, make a fighter great by denigrating his opponents."

The mother was a big bloomy-faced Irish woman, one step removed from Kilkenny. From her the six children learned the luxuriously freakish language, full of wild humour, that became the basic equipment of D'Arcy Niland the writer.

"We had a dictionary, too. When I was eight, Mum bought it for my birthday, at Kwang Sin's in Grey Street. We were so proud of that dictionary. Other people in the Glen had pianolas and ate the best cuts of meat, but we had the English language." In this family devotion to words, the writer may have had his genesis. However, although the young boy was already writing compositions praised by his teachers at the local convent school, his father severely discouraged him from "getting any grand ideas."

"How could you be a writer?" he'd jeer. "You need university education for that. It'd cost a thousand pound to make you a writer. I don't want to arg with you. You just get them ideas out of your head."

"His intentions were kind," D'Arcy recalled. "He just wanted to save me disappointment. But at the time it made me bitter as gall, determined as hell."

He began to contribute to Sunbeams, the children's page in the Sydney "Sun." It was conducted by Ethel Turner, a delightful woman who for many years had been Australia's most famous writer of juvenile books, a kind soul whose encouragement was the only thing that kept the lonely boy writing.

"We lived in a broken-down house with rats that every night ran a Derby under the floorboards. I can still recall the heartleap with which I'd hear the postman's horse cantering down the lane, bringing for me a letter imprinted with Ginger Meggs's face. My whole life hung on purple certificates from Sunbeams. Ethel Turner's interest and encouragement were an iron lung to me, and so were her successor's, Marie Marshall.

"I swore I'd be a writer, even though at the time I was apprenticed to a bakery. I was general doughboy, and learned how to make sausage rolls and custard tarts. I was captain of the football team then, playing five-eighth or centre. Miss Turner published a poem of mine beginning: 'Glinting like a web of gold On a Sapphire sea, Gleam the golden sunbeams bright, Dancing merrily!"

"You can imagine the chiacking. Fortunately a little earlier in a flush moment Dad had bought a Will Lawless boxing course and two pairs of gloves -I've always flattered myself I delivered the first solar plexus punch ever seen on the Northern Tablelands."

Shortly after this the boy joined a travelling boxing troupe which toured "all those towns that drop dead on the stroke of nightfall. I was the ampster, leading the rush of eager would-be contestants towards the board. Then I'd duck through to the back of the booth and around the front to gee 'em up once more.

"Here I gained my lifelong interest in boxers and boxing. I didn't take notes. All those people just went into my head, the rusty-necked fighters, the black boys with their possum eyes. When 1 began to write short stories. they were all there, waiting."

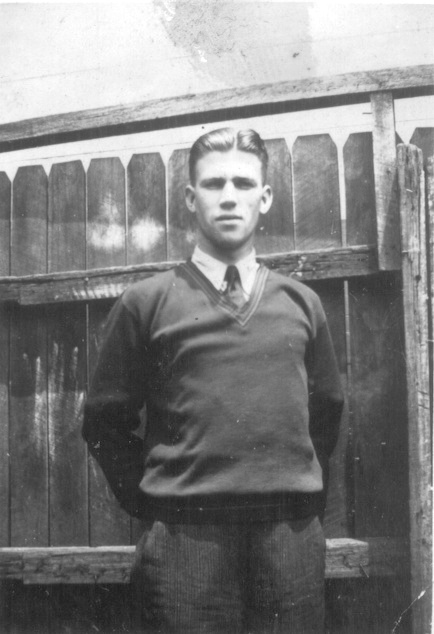

Not yet 16, he already had his man's height and weight. He was a nuggety boy with fine dark blue eyes and a broken nose which added interest to his already distinctive good looks.

By now he was aware that only in the city were there markets for a writer, other writers to talk to and learn from, books to be bought cheaply. As well, it was the tail end of the Depression, and the family had reached the end of its resources. So they decided to give Sydney a try. "Dad was away at a shed, and I was the man of the house. We went off like a flock of tinkers, things done up in swags and bundles, and Granny's old basket trunk she'd brought from Ireland. Mum carrying the new baby, and one of the brothers hooting like death with the whooping cough. So we took the train for Sydney."

The vast noise and confusion of the city almost paralysed the weary family. They managed to get a couple of rooms in Redfern. That night the boy went out into "the dark-houred city. She was a lion skulking. She was an old ship rolling around in sunless seas; like her sails and yardarms the shop blinds fluttered and creaked; the roving wind marauded her decks and blew with a hum in the iron rigging of overhead cables. A few thready drops fell past her lights . . ."

Next day he visited Marie Marshall at the "Sun" office and, with her recommendation, landed a job as copyboy.

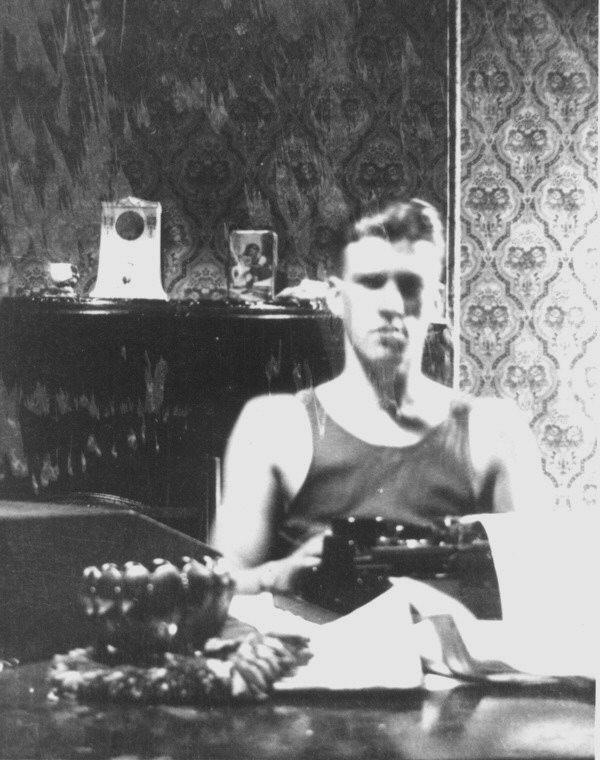

"A copyboy was a nothing but I was deliriously happy. I went to night school. I learned how to type. My brain was on fire; I could think of nothing but writing. Before and after work I ran all over the city like a blue-bottomed fly looking for hard news stories with which I could crash the 'Sun' columns and prove my worthiness for a cadetship. Once I got a pretty good story about a musical dog and a sub sent me to Eric Ramsden to have it bashed into 'Sun' style. He said: 'You! Boy! Do you want to communicate with people or don't you? Use a phrase like matutinal dithyrambs again and I'll skin you'.

"On my 17th birthday I was sacked. They said: 'You'll never make a journalist'. It was just commonplace retrenchment, I suppose, but for me the sky fell in."

For years afterwards when he was discouraged he'd repeat those bitter words: "You'll never make a journalist!" and get so enraged he'd sit down and pound out a story which would sell.

But for a long time no stories sold. He did, "casual nightwork proof-reading phone books. Even Dante missed that in the Inferno. I'd come home in the early morning through darkness and echoes, streetsweepers, lone cops, the homeless and forlorn. Friday nights I'd go to Paddy's Market, and penny by penny I accumulated hundreds of mouse-chewed books, Tchekov and Verga - they were my kings.

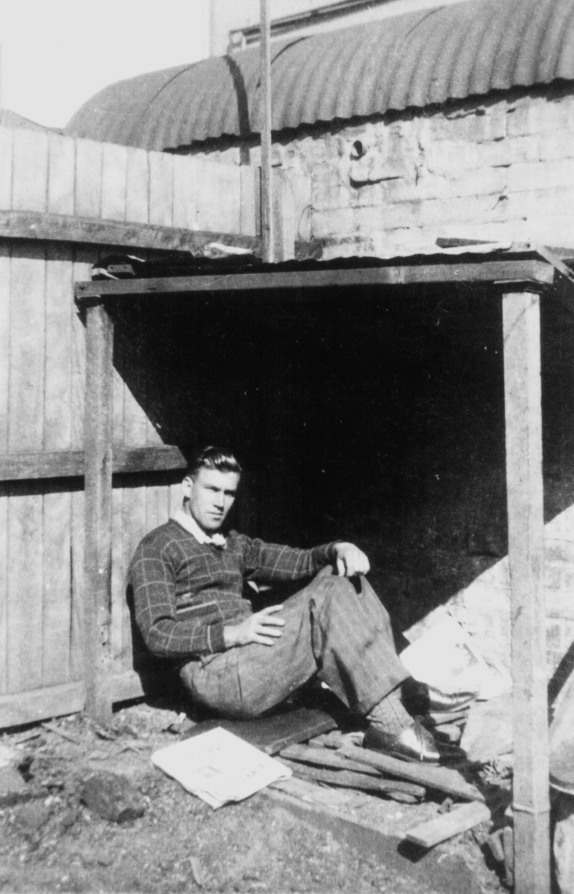

"In the daytime I sat out on the woodheap in our 6' by 10' backyard, writing. Kids from the rookeries roundabout used to nip over the fences like possums. I'd pay them a penny to scratch my head while I worked. It stimulated my brains. Then even the casual work ran out; I decided to go back to the country and look for work, go on the track. I packed a swag. Dad called it a shiralee."

Eighteen years later, when after a successful career as a short story writer he published his first novel, it was about a wanderer in those north-west country towns of his boyhood. This novel, which sold half a million copies in hardback in the English language alone, was The Shiralee.

It added a word to the language, and was so well-known that when D'Arcy Niland died, the London "Observer" reported it under the heading: "Shiralee Man Dies."

Text © Ruth Park [reproduced with permission], Photos © Niland Collection.