Part One IN SEARCH OF LES DARCY IN AMERICA

THE LES DARCY STORY is more than the brief biography of a phenomenal boxer. It is the history of a charismatic personality who became, along with Ned Kelly, one of Australia's two great non-Dreamtime heroes.

I thought of starting this piece this way:

The wrong person is writing these articles. But as the right one, the novelist D'Arcy Niland, checked out of this world some 11 years ago, I have no resort but to transcribe his tapes, decipher his interview notes, verify the dates, and use where possible his own text.

Then I thought: the hell with that.

During D'Arcy Niland's months in America, I was there as, well - assistant gumshoe, secretary, companion on a trail that was 45 years cold and that we feared might well be blown away on the wind, or mummified in brown-edged files - in newspaper morgues.

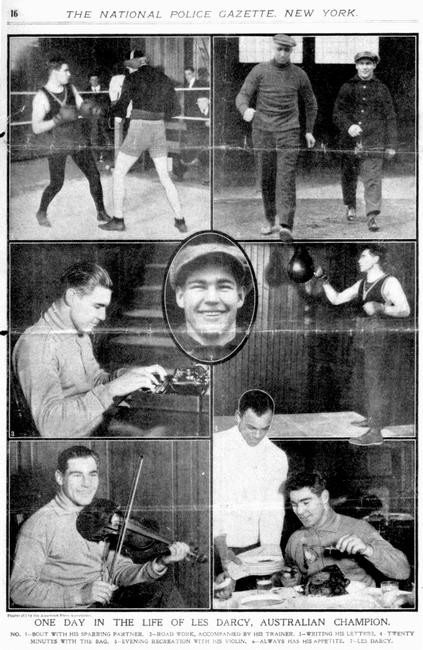

I imagine that those who read this piece already know something of Les Darcy. He was, in short, a young man from East Maitland, NSW, in whom heredity, physique and temperament had linked themselves to create a kind of boxing genius.

In six amazing years, he matured from a big barefoot kid, roaming around with his gloves over his shoulder looking for spars, to a dazzling prizefighter who seems never to have been fully extended.

In five years of professional fighting, from 16 to 21, he skittled some of the best middleweights in the world. He held the middleweight and heavyweight championships of Australia. Two of his fights were billed for the middleweight championship of the world, but were not recognised by America. In all, he had 44 important fights (Raymond Swanwick lists 50), losing two on points, one on a foul, and one when he himself was fouled in the fifth round by Jeff Smith and his second, Dave Smith, threw in the towel. The referee had not seen the foul and awarded the bout to Jeff Smith.

George Chip, Darcy's last opponent in Australia, was a terrific puncher and, two years previously, had held the middle-weight championship of the world. Chip had beaten iron man Frank Klaus, who had beaten Carpentier of France. Darcy chopped Chip down in nine rounds, completely demoralising this tough, experienced boxer.

A joyful and expansive character, modest and easy-going, Darcy was the idol of Australia. Then, in the middle of the nation's first bitter and often bloody conscription controversy, he slipped away illegally to the States. He wanted both official recognition of the world middleweight title, and the money which would secure the future of his family.

The year was 1916. He was 20. In: five months he underwent the complete human experience - adulation, treachery, persecution, vindictive abuse and death. As far as can be told, he didn't lose his cool from beginning to end.

Wherever old fighters gather in Australia, Darcy yarns are told. But would America remember him? We had no clue, for in all those years which had intervened since he died in 1917, in Memphis, Tennessee, no one else had followed the track of Les Darcy during his last embattled months. This can be said confidently, for in the vast collection of Darciana amassed by D'Arcy Niland, there is no intimation that anyone else ever attempted the task.

As our journey was made in 1961, the people then interviewed were old enough to have seen and known Les Darcy, so they are now almost all dead. I can see them yet, the black ex-sparring partners, the ruthless Roman faces of New York sporting executives, the crumbling old sports-writers.

Most of all, perhaps, the men of Memphis, with their soft accent, their endearing farewell, "Y'all come back now, you heah?" And I thought that if we could find Les Darcy anywhere it would be in that small Mississippi town of half a million population.

At that time D'Arcy Niland himself was dying gradually and with characteristic serenity, so I accompanied him everywhere, hunting up crummy Broadway offices where ancient promoters - always with some promising youngster from Wisconsin - sat like cold spiders, rich with lies and dishonest compassion for champions who ended with heads full of soup and broken mouths full of boasts that no one listened to any more.

There were once-celebrated sports-writers, who peered at us with bulging biblical eyes glazed over with tears and talked about that "poor, persecuted lad," when in the briefcase we had photocopies of articles they had written in 1917, steaming righteously about traitors and slackers and cowards, and the God-given privilege of a fit young man to join the colours.

This, in spite of the fact that the underage Darcy had twice attempted to enlist, and his oft-reiterated statement that all he wanted was five fights with worthy opponents, and then he would enlist either in the States or in Canada.

"And at the same time, Hollywood and Broadway were hopping with British actors who had cleared out at the beginning of the war, not to mention several Australian boxers who had gotten permission to leave their home country without trouble," commented Jimmy Breslin, now probably one of the three most famous newspapermen on the East Coast, and even when we met him, a vivid sports reporter.

Meeting James Breslin was our first break. A literary agent mentioned a bar where he might be tying one on - he'd, lost out on something, girl, job or award - and so D'Arcy went along to see. Sure enough, there he was, a handsome New York Irishman, morose as a badger, but ready enough to warm up to someone from "Where? That place? You got good pugs and swimmers down there."

He quickly dispelled D'Arcy Niland's fears that Les Darcy might be forgotten in America.

"He was plundered, that poor guy. He stayed on America's conscience. You couldn't expect him to defuse a situation which was politically emotive, and complicated by slime-green bitchery. Once Tex Rickard took away his sheltering arm and money, he was helpless. You can't blame Tex, he was a promoter, athletes were just so many pounds of valuable meat to him." Then he said a perceptive thing.

"That Darcy wasn't dumb, for all he was such a kid. He was a kind of frontiersman in his head, that was all."

He gave D'Arcy some addresses of old gyms down near the Battery, where the old pugs hung out, and introductions to people like Nat Fleischer, scribbled on the back of his card. Gene Tunney was in town, he said. He had a fancy for Australia, maybe because his pen company, Eversharp, did so well there, so go see him.

Like most people in the States, Jimmy Breslin referred to Les Darcy as "Less." The forename Leslie seems rare, and, from the beginning, Americans often thought the boxer's name was short for Lester. In the newspapers of 1917, he is repeatedly referred to as Lester Darcy. Gene Tunney, however, had the name right. He looked like the kind of man who would make sure of the accuracy of anything he pronounced upon.

Dignified, astute, probably 60 or 50, Tunney still had the open-faced charm of the classic "college boy" boxer who took the heavyweight championship from Jack Dempsey in 1926. He was kindly, too, and talked for some time about Darcy.

"I think you'll find that he's well remembered in this country," Tunney said. "He was not only a boxing prodigy, a nonpareil, but he incarnated the hero principle as well. Young gladiator stuff. He was just a kid when he defeated some of the best middleweights this century ever produced.

"If he had lived - to 24, say - he would have been a marvel of marvels. As it was, I would call him the best middleweight of all time. See if Mr Dempsey doesn't agree with me."

We walked down to Jack Dempsey's unpretentious restaurant, near 49th St. D'Arcy said, "I hope that the old Les heard that."

I said, "I hope the old Jack offers us a cup of coffee." We were nearly always ravenous, for we had just enough money to get by.

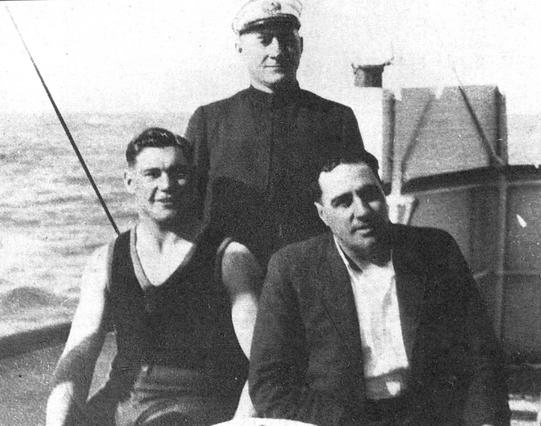

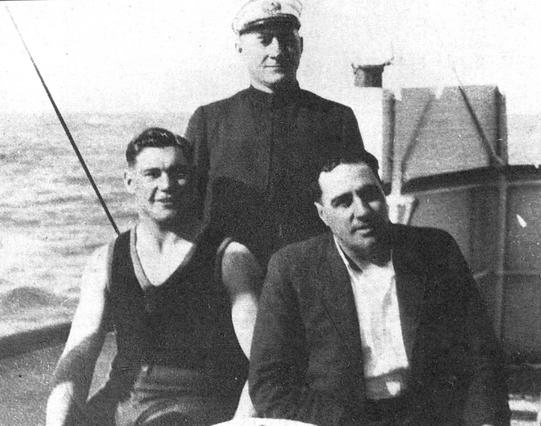

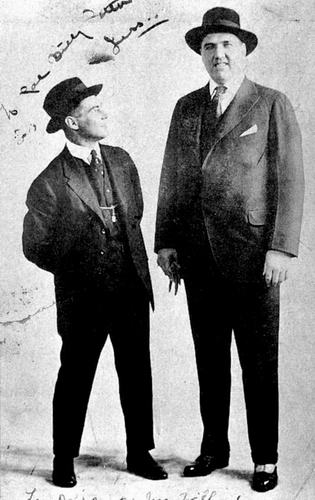

D'Arcy Niland and Jack Dempsey 1961

Thank God, the old Jack offered us a hamburger along with the coffee. Meeting him was an event for me, for he had been my father's criterion of manhood. As a child, I had constantly heard horses, dogs, pigs and Maoris described as "game as Jack Dempsey," "wild as Jack Dempsey," "hungry as Jack Dempsey."

And here he was, not only my father's but Gene Tunney's hero principle, in the flesh. In some mysterious way a hero resonates with the public; you can feel it sure as you can tell heat from cold. Dempsey helped us understand the Darcy myth. Tunney, of course, understood it well. He had defeated Dempsey twice, and the public never forgave him for it.

Flawlessly dressed, mighty paws manicured, with sleek jaguar head and Inca eyes, Dempsey chatted to us hospitably about his life as hobo, fighter, restaurateur and "Less" Darcy.

"Never saw him myself. There was a possibility we'd meet, you know, when it became obvious that Carpentier wasn't going to come fight him. So some of my handlers went to Goshen, where he gave an exhibition spar with Fred Fulton.

"Believe, me, Fred was a dinosaur, a nice dinosaur but twice as big as Less. But Less skittled him. He was one hell of a fighter. They sold him a bill of goods, Less. He got sick and I think he died of a broken heart.

"Who are we to say about the way he left Australia? Easy to throw stones. I was called a slacker later, and so was Jess Willard."

"Do you think you'd have licked him, Jack?"

"I reckon. But I tell you this straight: I'm working on the saying that a good big man can always beat a good little man. Less and I were the same age bar a few months, but he was giving away nearly 45 lb in weight, and nearly 7 inches in height. But, who knows? He was a game boy, I wish I could have shook him by the hand."

While we were interviewing people we were also working several hours a day at the New York Library. Stone walls, richly inlaid and intaglioed roof with gilt encrusted panels, a Renaissance effect. But a pain in the neck to work in. No air conditioning, everyone in shirt sleeves and glistening with sweat.

Not many libraries nowadays will let you examine old newspaper files, because the paper gets so crisp with age it can literally fall into a heap of scraps, like flaky pastry, in your hand. So I had long sessions at the microtape viewer, that demoniac contraption that drags out your eyes to waggle and bounce as if on springs.

I was examining the New York Times files, and it was curious to know that these very headlines were read and discussed enthusiastically by US fight fans SO long ago:

"Darcy Coming On Cushing."

"Les Darcy May Battle Carpentier."

"Wild Race Among Promoters To Reach Famed Antipodean First."

Most interested, I fancy, were the contenders for the title which had been in dispute ever since the murder of the previous holder, Stanley Ketchel.

No other overseas athlete had ever been greeted with such extravagant excitement. However, the level headed Darcy had never identified with his popular reputation, and the mad scramble of entrepreneurs to sign him up 'was described in his plain-man manner to his friend, Will Lawless, of The Referee:

"Soon the oil boat (Cushing) was surrounded by tugs filled with fight promoters and vaudeville managers, newspapermen, photographers and others - all clamouring to see us. It was as funny as a circus. The quarantine officers came alongside, and we had to sign our names in the book and show about $25, but we never went into quarantine on Ellis Island. They say anything in the papers."

Anyone who tackles history or biography must be prepared to read old newspapers by the thousand. You go through them, day after day, looking down bug-eyed from your high perch in the future, watching a story build up - the inaccuracies, the downright lies, the deliberate propagandist blandishment of the reader. You see the lies consolidate, or fall to pieces in the light of your hindsight.

In Australia, misinterpretations of canards concerning Les Darcy lie around the ground like bird lime for the biographer to stick in, and here in these old brown newspapers one could spot where many of them originated. The stories were so contradictory and imaginative that it was easy to see how confused Australians must have been by the hysterical cables from New York correspondents.

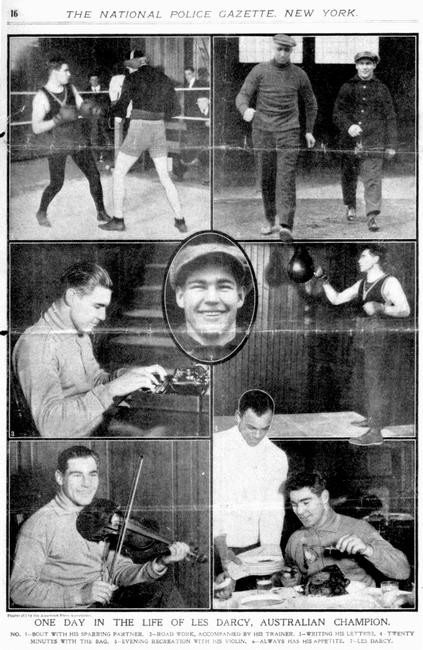

Whom was Darcy going to fight? Who was his manager? Tex Rickard, who was evidently advising him? Jack "Doc" Kearns and his partner, Jack Curley, who were threatening to sue him for breaking an already existing contract, which was never produced? Mr E. T. O'Sullivan, who had stowed away with him on October 27 in the Hattie Luckenbach? Why hadn't Darcy gone with his inseparable mate, Mick Hawkins, who had discovered him and been trainer and rubber ever since?

Les Darcy and E.T. O'Sullivan on passage to USA, 1916

As it came out later, Hawkins had intended to leave with "my boy" but his father died, and he promised Darcy he would follow him as soon as possible. Darcy left him the money for his steamship ticket.

But who was E. T. O'Sullivan? He was variously known as Ted, Tim, Sully, and nearly always as Sullivan. Even Darcy, in his early American letters, sometimes refers to him as Sullivan.

He was a "sporting blood," a strapper around racing stables, a handler of one or two young unimportant boxers, an occasional referee, a hanger-on in sporting circles, not very well known by anyone.

Some writers of the time frankly say he was a "shanghaier." He had contacts; he could get you out of the country for whatever reason you had. Darcy paid £75 each for himself and O'Sullivan to stow away on the Hattie Luckenbach, and it seems pretty incontrovertible now, that the captain was in the know. O'Sullivan also was of military age, and anxious to get out while the going was good.

Why would Darcy go against the advice of his best friends and tell so few of his plans - his family; the O'Sullivans of the Lord Dudley Hotel; his sweetheart, Winnie O'Sullivan; his teacher and adviser, Father Coady; Mick Hawkins - and go off with this dicey character?

The answer is that there was no other way he could do it. He had been refused a passport though his solicitor had made application time and time again. He did not know why, as he had offered to post a large bond against his failure to return in six months. Other people in his age group were getting them, as Jimmy Breslin pointed out.

He had the choice of clearing off to America or finishing his career at its prime because Stadiums Ltd, caught up in the fearful public furore both for and against conscription, had, with Darcy's consent, announced it would give him, at the expiration of his current contract, no more fights until he enlisted.

Without conscription (and both referendums failed during the first World War), enlistment was a man's personal choice. But there was tremendous pressure, emotive (don't let your pals down, look how many of them died at Gallipoli...), political (Prime Minister Billy Hughes had in his rash, inflammatory way promised the British Government heavy reinforcements for the AIF) and moral.

There were numerous ways Darcy could have compromised with all these stresses. He could have done an Elvis. The suggestion was put to him many times, not only by Australian military authorities but by Canadian ones. He could have enlisted - wonderful PR for others to do so - and been tucked away in some safe job as physical instructor.

He could have enlisted and remained in Australia and been given extensive leave for boxing. This also was offered.

Why then did he not compromise? Because, anomalous as it seems of a man who was called traitor, runaway, cur, he believed in enlistment, and also in conscription. Many of his dearest mates had been killed at Gallipolli. When he joined the Army he wanted to go to the front, as the brilliant tennis star Anthony Wilding had wanted.

Darcy said this over and over again. He just didn't want to go until he had the opportunity for a few fights in America, so that he could consolidate his family's future. He felt, as he had felt since he was a small boy, that his first duty was to them.

In the old New York newspapers, one could also sense the resentful reluctance to get into a war which did not concern the States, and characteristic American anxiety about the nation's correct position in global politics.

In fact, when Darcy arrived, the country was already secretly committed to entering the war, and did so, the following April. Conscription was never submitted to a plebiscite as it was twice in Australia; it became a fact of life when America threw its military weight in with the Allies.

But conscription was an issue as touchy as a boil. The question of moral liberty was an itchy one (it did not start with Vietnam demos), and this famous boxer's ambiguous departure from a homeland already at war was eagerly seized upon as an argument both pro and con.

A moonlight flit by Joe Blow would not have raised an eyebrow, but because of his eminence Darcy became the focus of every confused attitude towards war - patriotism, compulsory service, liberty, martyred little Belgium. Though he had no choice, psychologically Darcy could not have timed his entry into the States worse.

The news of Darcy's flight, from Australia had reached the States by faster ships than the Hattie Luckenbach and the Cushing, the Standard Oil tanker to which he had transferred in South America. Stadiums Ltd had rushed its story to the New York papers long before December 23, when Darcy arrived.

"For the last two years, this great boxer's name has been a household word. Les Darcy has been the flappers' ideal and the schoolboys' hero. But alas, the scales have fallen from their eyes and Les Darcy, instead of being looked up to, will in the future be looked down upon."

This came from the boxing circular always republished in American sports columns. It was written by Snowy Baker, then owner (though possibly only part-owner with the builder and original proprietor, Hugh D. Mclntosh) of Stadiums Ltd.

A later circular stated: "Owing to Les Darcy's unpatriotic actions in clearing out of his country at a time when he should be doing his little bit along with his Australian comrades, it has been decided to strip him of his middleweight and heavyweight titles."

As a matter of record, all Darcy had done against the law was to contravene the War Precautions Act. Still, one must see his act against the emotional climate of 1916-17.

There was also a suggestion in government circles that Darcy's property be confiscated. Wild rumours about the value of this property ran around, £100,000, and so forth. In fact, he had put nearly all he had saved into a house and farm for his mother and elderly father. His estate, when declared probate after his death, was £1,800 (Will Lawless says £1,700).

Hugh D. Mclntosh's paper, the Sunday Times, launched the first broadside in November, 1916. There's a good deal of it, classic flak: "For the fellow who bolts in a dreadful funk when he begins to deem it possible that his duty may be thrust upon him, there can be nothing but disgust and scorn."

This, in spite of the fact that Mclntosh himself had, in the early days of 1916 - far closer to the national horror and grief over the bloody debacle of Gallipoli, offered Darcy a contract for £5,000 for five fights in America against unnamed opponents. From what Kearns said later, one gets a spooky feeling that this contract was to be hawked to Kearns and his hardboiled associates, a powerful managerial co-op and rivals of Tex Rickard.

Neither Mclntosh nor Baker, though in the required age group, enlisted, though Baker later formed a highly publicised "Sportsmen's Battalion."

In Father Coady's words, Stadiums Ltd had lost a goldmine and were out for blood.

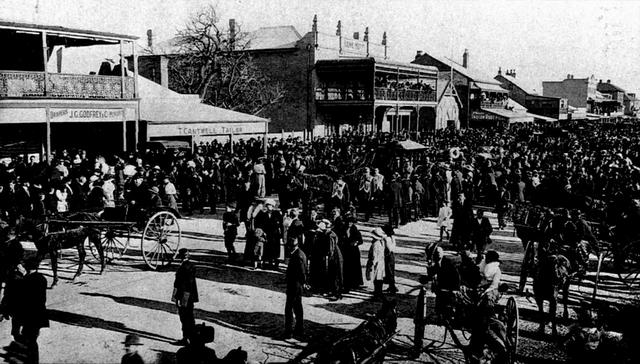

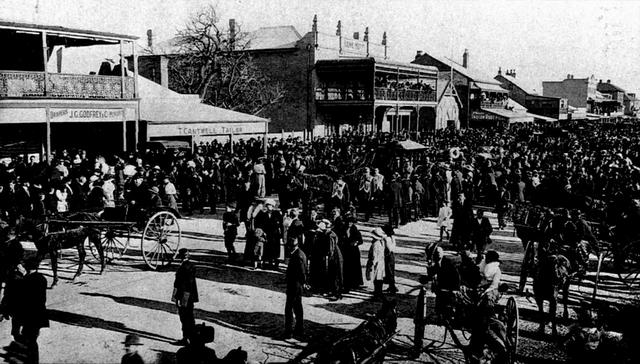

Australian papers, all of which had. taken a strong line either for or against conscription, followed the high tone of The Sunday Times, and chose to speak for the majority of the Australian people, who really had no chance to speak for themselves until Les Darcy had died and they were able to demonstrate their real emotions at his funeral.

"The majority," announced Sydney People from its papal throne, "said in their hearts, you're a shirker, Les Darcy, and we thought you a real man."

Les Darcy, though at the time he was fully aware of Baker's involvement - however unmalicious it has been claimed to be in this campaign, makes no reference to it in a letter. "I have a chance, right now, of setting my family, on their feet and can do it in a short time, and then I don't care what becomes of me. I still intend to enlist, Mr Baker, and if I have a few fights over here, and if the authorities over there in Australia will overlook my wrongdoing, I will return and enlist in the Australian army."

This letter was published in the Australian Referee, also owned by Hugh D. Mclntosh, and was followed by a squelchy addendum, perhaps, perhaps not, written by Snowy Baker: "The fact of a sinner confessing and expressing sincere contrition, and also promising to do all that lays in his power to make amends, has moved many a stony heart to favourable consideration. The matter rests, with Mr Pearce, the Minister of Defence."

New York readers of the sports pages were well aware of the flurry in Australia, and Les Darcy knew this. He had scarcely stepped on American soil before he made a direct and simple statement in the terms with which he expressed his intentions to Snowy Baker. "I do not want anyone to consider me a shirker for leaving Australia, just as soon as I have earned what I consider a sufficient sum to keep my family in comfort I shall go to Canada or England and enlist."

Great controversy was to surround Darcy in the States, but it did not happen all at once. The boxing promoters knew that they had the diamond ice cream within their grasp, and fantastic offers were made for this match and that.

Both Darcy and O'Sullivan knew that these offers were dream-stuff, created solely to get the young fighter's name on the dotted line. They accepted none. Tex Rickard, on the other hand, who had established the two newcomers in the Broztell, a comfortable Edwardian hotel on East 27th St, said downright that he was not Darcy's manager:

"All I desire is to get his signature to box for me, and that will end his connection with me. Naturally I should not care to have him get into the clutches of the harpies who habitually fleece boxers, and I shall do my utmost to see that he gets a capable and conscientious business manager."

Darcy was entranced with New York. He had never seen snow before, and, of course, New York is a great city at Christmas.

The New York we saw in 1961 was considerably unlike the megalopolis of today; more like the one Darcy wandered around, like an old picture with the paint peeling off here and there, showing other objects and territories, other human intentions aborted or superseded.

He rode the streetcars and the underground, fooled around in the snow, started training at Billy Grupp's gym on 116th St. Darcy was always able to cram an incredible number of things into one day.

Almost from the time he arrived he worked out daily in the gym, for he had put on weight on board ship and was well over the middleweight limit. He skipped, punched the bag, worked on the pulleys. Wisely, Tex Rickard had advised him not to spar in public.

Someone called Jack Moore that we met in a derelict, crow-poor gym had seen him work out at Grupp's. "Natural-born fighter, fine-looking, well-built fella. Nice head of hair. Funny thing, though."

"What was funny?"

"Said he'd die young. Came straight put with it. It was one of those things, maybe, a premonition. That was why he was so desperate to get into the big league quickly."

At the time, D'Arcy Niland did not give this much thought, beyond commenting that the war had indeed got Darcy, though not with a bullet Some weeks later, in Philadelphia, we found a January 7, 1917, quote from Darcy. "Les Darcy, the marvellous Australian champion, is a fatalist. He believes his end is not far off. He is prepared to die.

"'My people come first with me, even before my country. I don't believe I'll survive the war. I expect it and I'm ready for it. I'm ready to do my duty, but I would be shirking a duty if I gave my life before I provided for my own. So while I'm here I'll fight anybody they offer bar none, the devil himself if need be, to get money."

In the filthy, three-quarter-dead gyms in New York and Chicago we gathered a heap of endearing anecdotes for the book on Darcy that D'Arcy Niland hoped to write, but pretty useless for this article, so I'll touch only on one.

In these establishments the walls were sodden with that sweat stink that lasts forever, the towels stood up by themselves. The gyms were frequented only by aimless youths slamming the split punching bags, and gimpy old guys who had nowhere else to go.

"Lose da broad!" they commanded fiercely as I entered this decomposing man's world.

"The broad stays," said D'Arcy Niland, and I stayed, melting cryptically like an insect into the dereliction and the melancholy, while the old pugs with their scabby hands and their, faces of Renaissance hit men, retold fights, bell to bell, moving stiff shoulders, throwing short aborted jabs, snuffling through gorilla noses.

They'd all heard of Les Darcy. "It ain't true that we poisoned him. He done got pneumonia."

The old boxer, Sugar Boy, said, "Mr Less, he a draft dodger."

"Naw," said someone, "it was for the reason of some big guy with a lot of pull in Australia got the ear of Governor Whitman and so he was banned from fighting in this State. That Whitman, he hated pugging, some kind of nut."

Governor Charles S. Whitman certainly was anti-boxing, almost to the point of obsession. He described it as coarse and brutalising and had done his best to push through legislation proscribing it in his State.

When Darcy was given such a royal reception in New York, Whitman took it personally, describing it as a slap in the face, and a bad example to prospective American draftees, that a deserter, as Darcy was at first erroneously called, should be given such adulation.

At this time, many States had outlawed prize fighting, so professional promotion became sub rosa; the bouts were advertised as exhibitions; purses were privately slipped to winners, and no decisions were given except by the newspapers.

Only in States where boxing was allowed could championship title fights be held. Al McCoy, whom Darcy was soon booked to meet at Madison Square Garden, had won his title this way.

Nevertheless, boxing was legal in New York State, and Whitman's sudden thumbs-down on Darcy, but not on other boxers, can be explained only by some outside pressure.

The ban was announced on March 3, 1917. It must have been a shocking blow, not only to Darcy, but to Tex Rickard and his associate, the oil millionaire and speculator Grant Hugh Browne. At the time Darcy was training at Browne's palatial quarters at Goshen, some way outside New York. He had been offered $30,000. for a 10-round bout, and naturally he was jubilant.

Browne had a long association with the US Army, as he had a contract for provisioning Army horses and mules. It was his belief that America's entry into the war was imminent, and that the Federal Government of Australia, desperate for reinforcements for the AIF (and having a battle to get them at that time), had requested its ambassador to ask the US governors to put pressure on Darcy as an example to other "shirkers."

There is no doubt that in Australia grief, fear, anger, and confusing propaganda formed a critical mass that blew, apart both politically and popularly several times.

We know, for instance, that employers constantly dismissed men of military age, thus causing a kind of involuntary enlistment among the unemployed. One can scarcely believe that every employer was so crammed with love of the Mother Country that he would put off a young, fully-trained mechanic and take on his aging dad instead.

There are high smells in every trade at this time, and it is impossible to dismiss the conclusion that both State and Federal Governments (particularly the latter) were involved.

In order to begin training for the McCoy bout, Darcy had, on February 11, cut short his vaudeville tour with the Freeman Bernstein theatrical set-up.

Regrettably, we were never able to track down - if indeed he were still alive in 1961 - Freddy Gilmore, an old opponent and friend of Darcy from Sydney days, who was Darcy's sparring partner on this tour. So we have few details of the tour except that it was a fizzer.

In those times vaudeville or stage performances by celebrated athletes were commonplace. Everyone from John L. Sullivan to Hackenschmidt, the great wrestler, had toured giving demonstrations of their skill.

The Bernstein tour began in Connecticut on January 11. Perhaps Tex Rickard thought it would get Darcy away from the storm of would-be managers, promoters and pests, and the snowballing bad publicity sparked off by the yelps from Australia.

Darcy was offered 15 weeks at $2,500 a week. He was short of money. Rickard had advanced $5,000 to O'Sullivan for expenses, and the tour might have seemed an easy solution to the repayment of the debt.

Darcy had done a tour in Australia and enjoyed it, regarding the whole thing as a great lark and a chance to see the country. Besides, it was fairly obvious by the first week in January that Georges Carpentier, whom, it seems, Darcy wished to meet above all, was not going to come to America.

Mick Hawkins arrived in San Francisco in late January, apparently not having had any passport trouble, though he was a fit man of military age.

The desultory conversation of the old men in gyms in New York and Chicago, D'Arcy Niland's complete absorption in it, made me aware once again that it's almost impossible for a woman, however observant, to get any real gut-feeling about how men look at fist-fighting. It is the most ancient and natural form of man-to-man combat, and the epitome of the masculine principle of overcoming an opponent solely by strength, courage, and bodily skill.

Of course, when you live with a fight aficionado like D'Arcy Niland, who not only wrote about boxing but had in his youth been a keen amateur as well as aggressive "grassfighter" there's some unavoidable osmosis, but not the absolute comprehension and almost total recall.

In conversations with men like Jack Dunleavy or Jimmy Sharman, D'Arcy could say, right off the board, things like: "Chip crashed to the canvas on hands and feet. Darcy came in like a steam-engine, slipped inside a left lead and slammed a right to Chip's heart.

"In the final round, the American landed a left hook square on Darcy's mouth. Darcy moved back on his right foot and, as Chip whipped out a left lead, crossed his right. Chip went down head-first; he tried to get up at eight, but no go."

This, of a bout in 1916, Darcy's last professional fight.

In spite of some absorbed knowledge, I knew I would be a dummy to try to assess Darcy professionally. It occurred to me then, however, that in America, Darcy was not a boxer - he had only two semi-private spars - because he had ever been allowed to box.' In the States, as nowhere else, he had been a person.

So I thought, okay, you tend to the boxing side, mate, and I'll look at the character. What made Les Darcy what he was, how did he come to die so young, what did the ordinary people think about him in spite of the power of journalistic untruth.

We were close to being skint, New York was getting hot, and D'Arcy Niland was looking grey-skinned and getting pains in his legs and chest - a bad scene in a coronary case.

Added to that, we had phenomenally bad luck; it was almost as if we were intentionally thwarted in our attempt to talk to old opponents. Fritz Holland settled in New Zealand. Jimmy Clabby had disappeared from view, some thought in Western Australia, Jeff Smith was now a businessman in Levittstown, New Jersey, under his true name of Jerome Jeffords.

After numerous promises to meet and talk with D'Arcy Niland, he evaded him, perhaps because of embarrassment over his reputation as a dirty though brilliant boxer. The two Darcy fights ended with brazen fouls; Smith was disqualified from ever fighting again at Sydney Stadium, and his share of the gate was withheld. He sued for it, lost the case and skipped to America, leaving a great many unpaid debts.

Game Eddie McGoorty had taken the downward path so common to pugilists - booze and frightful hidings ending his life at 40. He made several visits to Australia. He said, "Down there they treat the loser better than they do the winner here."

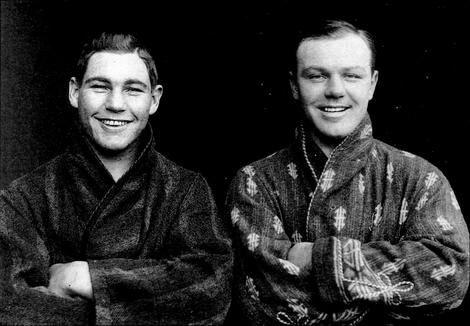

Les Darcy and Eddie McGoorty

We could not trace Buck Grouse and, of course, saddest of all, Freddy Gilmore, who had been at Darcy's deathbed. All we knew was that he had given the game away after the death of his friend and gone into the building trade in Chicago.

We met no one who had seen Darcy fight, even on film. Of course, Jack "Doc" Kearns had, when he took Billy Murray over to Australia; saw him whipped, and did his eloquent best to persuade Darcy to come on the American circuit and pick up a bit of the gelt lying around. From his luxury home in Florida he answered civilly, but by that time we couldn't afford the trip.

It was either "Doc" Kearns or Memphis, and as Jimmy Breslin said, "Doc Kearns has been as documented as a man can be. You don't have to see him. He was with Soapy Smith in Alaska during the gold rush, you know. Soapy would steal his brother's eyes-' and pawn them, and then poke the sockets in, and Doc was his faithful disciple.

"He is a corsair, he has more sass than a dozen. His real name is Leo McKiernan. To Doc, in his big days, there was no inhibiting authority. Besides that, he had all the magic tricks. He invented publicity.

"Pity Les didn't go to the States in 1915, when Kearns was so keen that he should. He would have made a pile, and no trouble. But Les had heard of his reputation, he was scared of being chewed up and spat out. Everyone had warned him against American promoters, especially Doc and his ilk. As it was, Kearns took against Darcy - he never let up on that boy. He saw millions disappearing out of his grasp."

Kearns must have been a vivid old guy, and we would have liked to meet him. He died a couple of years later, bust but content. He was a genuine rogue guru of the fight game.

So we went to Memphis, by bus, and by then we hated buses - back to motels and semi-starvation again, long trips among the lolling heads, the open mouths; the lemony light that soaks the vitality out of the already fatigued and dislocated; early-morning arrivals at drear terminals in nasty parts of town.

We felt grubby and lousy and hopeless about whether we'd ever get Les's story right. We wanted to travel by day, to see the countryside that is constantly mentioned in the many postcards and letters Darcy sent home to his friends. He was a farmer at heart, keenly interested in animals and crops; the Irish countryman in him, I suppose.

I once asked Winnie O'Sullivan, his fiancee, whether she thought, if he'd lived, he'd have settled down as a tubby publican as so many boxers do - should they survive their brief and perilous careers.

She smiled and said, "No, he would have been a farmer. I was agreeable, the man mattered, not the place."

But mostly, because of the cheaper fares, we travelled at night. During these abominable journeys we pored over our notes, re-ran the tapes. It was a stressful time. D'Arcy Niland grew tenser, obsessed with the desire to "get the old Les right."

Sometimes I felt I was travelling with two men, both with identical heredity and background, the same indomitable stubbornness - one with black hair and blue eyes, and the other with brown hair and grey eyes "of striking clearness and directness."

Knowing that D'Arcy Niland was going it too hard, I was often spooked. Biography, if you're honest, is no snap job. It isn't Polaroid stuff. It takes time and backbreaking patience.

What obscures your vision, though, isn't the years, but oldthink. You look backwards through curtain after curtain of changing mores and attitudes, like sheets of soiled Perspex, through which you can see your subject moving, all right, but often in a dreamlike blur.

And Les Darcy's life had such a rapid flow. There was never a moratorium for him, to delay momentous decisions, to reconsider the situation. He was born into shocking poverty, and was the close-knit family's breadwinner from an early age. Moreover, he was the one they all psychologically depended upon ... the lovable, generous, often ill mother, the many little children, the elderly father who was not equipped in any way to cope.

And if he had this thing, this belief that he would die in the war, what urgency he must have felt. He was no fool, he knew that a boxer's prime time is short, that he could easily end up like Griffo.

One night in some dump in Atlanta I tried to persuade D'Arcy Niland to cut the arduous business short and go on to England, where we had business waiting. He said, "No. If anyone is going to tell the truth about Les, I am. Ned Kelly and me, we understand him. I was my mother's husband when I was 12, too."

He had given the word its classic meaning - the householder, the provider, the one who shouldered the responsibilities.

"I think we have all the clues to Les's character. He always told the truth, but the truth seemed just too simple for people to believe. Not even the sportswriters misrepresented what he said, though they misrepresented everything else as if they were writing fiction.

"On the other hand, we know that E. T. O'Sullivan was a liar. Let's look more closely at him."

© Ruth Park 1978, 2010 [reproduced with permission].

Read Part Two

Part Two THE AWFUL DAY LES DARCY DIED

THE JOURNEY from Atlanta to Memphis was an important one in D'Arcy Niland's and my search for Les Darcy in America.

During that tedious time we examined all the interview and printed evidence about E. T. O'Sullivan, who accompanied the young boxer on his illegal skip to the States in 1916. We stuck to O'Sullivan's own words, not other people's. Also, we analysed the almost universally believed story that Darcy died of a broken heart.

The broken heart syndrome certainly exists, and it would be a romantic end to a hero myth, but it just doesn't jive with what we know of Darcy's character.

Many people who knew him, like Father Coady of Maitland and Taree, said he died of despair at the cruel injustice that was meted out to him. But the people who knew him in Memphis, the doctor, the priest, his friends who were at his deathbed, said no, "He never was as great as he was when sickness marked him down."

Let us first look at the enigmatic O'Sullivan, who has been described traditionally as everything from a tinhorn gambler to a crack footrunner.

One of the many intriguing things about O'Sullivan is that though he obviously was of military age and had also stowed away without a passport, there is not a single newspaper reference (that we discovered) to him as "a slacker." As D'Arcy Niland said, with rare bite, "He probably had the nous to develop a TB lung the day he landed from the Cushing."

O'Sullivan cannot be blamed for Darcy's breaking the War Precautions Act by leaving without a passport, and Darcy never blamed him. He was well paid for his part in the caper, and he lived the life of Riley as long as Darcy was being courted by American promoters.

Was he indeed Darcy's manager? It is true that in two interviews we found Darcy himself speaking of O'Sullivan as his manager. This may have been a journalistic error or a slip of the tongue.

Darcy's actual statement, on December 26, three days after his arrival, was: "I am not linked with Mr Kearns, Mr Curley, or anyone else. I never had a manager even in Australia.

"When I first started boxing, Mick Hawkins acted in a semi-official capacity. He was my trainer up to the time I left home. Then I had Dave Smith with me for a year.

"At the expiration of the 12 months, I went on my own. My mate here with me, E. T. O'Sullivan, has been associated with me for about a year. Nobody at all has the slightest managerial claim, written or oral, on me."

In Australia, Darcy had been warned by good men like Jack Dunleavy, who had had a rough time in the States a year or so before, that a good manager was a necessity. He'd been told by Dave Smith, a man of great integrity.

In America, Jimmy Dime, manager of George Chip, and a loyal friend of Les, practically went on his knees to beg him to get a manager. "You'll be butchered. It's not like Australia, you know."

Why did he not take a manager from among the many who besought him, and who, undoubtedly, could have not only arranged big fights for him, but sweetened the newspapers that began to slam him after Snowy Baker's circulars were published?

He was not dumb; he was not ignorant of the dog-eat-dog situation in America. He was not too mean to pay a manager, as his enemies often said. He had raised something like £70,000 in Australia for the Red Cross before he left, giving generously to the fund not only in time and boxing exhibitions but in money.

One can only conclude he was wary of managers, especially of Kearns, whom he had met in Australia in 1915. Kearns had pressured him to accept a boxing contract. Briefly he decided to accept, seeing in it a way out of his dilemma, and then turned it down on advice from Stadiums Ltd, and the tales he heard of Kearns' ruthlessness.

Even in Australia, Kearns had billed Darcy for $100 for cables and "general expenses" related to the discussions of this unsigned contract.

Tragically, Darcy did not take on a manager until too late, in Memphis. In January, in New York, O'Sullivan went on talking big, proclaiming he was Darcy's manager, most loudly during Les's absence on the Bernstein tour. "I've looked after this boy ever since he was featherweight champion of Australia." In this unique sentence almost every word is untrue.

People, however, believed him, even Tex Rickard, who advanced him $5,000 to cover expenses. This the canny O'Sullivan, through astute legal work, managed to hold on to. It must have been one of the very few times Tex copped the wet end of the mop.

The O'Sullivan story is very much involved with the vital dates of Darcy's life in America. The two young men arrived on December 23, and Darcy left for the vaudeville tour on January 11. Mick Hawkins arrived at the end of January, 1917, and probably joined "my boy" at once.

O'Sullivan was still in New York, playing the powerful kingpin, talking fantastic sums. He did not consult Darcy about the arrangements he had made, and Darcy was annoyed and disturbed, as he maintained O'Sullivan had no right to sign contracts on his behalf.

Having terminated his vaudeville contract on February 11, Darcy returned to Grant Hugh Browne's training quarters at Goshen. Here he seemed extremely fit, although he was treated for a sore throat the doctor said was caused by inflamed tonsils.

As soon as he returned to New York, Darcy must have broken with O'Sullivan. He had already had a confrontation with him in Chicago.

Sully lost no time in getting the ear of his newspaper friends. He was a good looking, amusing, quickwitted man, and one of the many newspapermen who had taken a liking to him was rough old Bat Masterson - once marshal of Dodge City, professional gambler and boxing promoter, and for nearly 20 years a columnist and sports editor for the New York Telegraph.

I've always had a soft spot for him because he fell dead at his desk, and the last words in his typewriter were, "Life evens out. The poor get the ice in the winter and the rich get it in the summer."

Bat Masterson was only too ready to assist Sully in the planting of stories of Darcy's dishonesty, ingratitude, treachery and so on in papers all over the country. It was great news stuff and was generally published. Bat Masterson's own material was vitriolic. Darcy's only published reply, aside from interviews, was published in the New York Sun, where Nat Fleischer was sports writer.

It is too long to reproduce. I give relevant extracts: "I wish to contradict the stories sent out by Mr E. T. O'Sullivan regarding our split. Had he acted fairly in the matter he would still be with me as trainer and pal.

"He states that he had a contract signed with me calling for a third of my earnings, and in another paper says the contract called for 25 per cent of my earnings.

"In one paper, he states the contract was lost on board the ship, and in another he says I tore it up. We had no agreement of any kind saying I was to give him any percentage of my earnings.

"We left old Australia seeking our fortune together, and O'Sullivan well knew that if he did right with me he would be well taken care of. When I refused to give O'Sullivan his demands the other day, his parting tip to me was that he would make me wish I was back in Australia, the way he would roast me in the papers."

This he did, and with great skill.

Fleischer told us that Darcy assured him that Ted Sullivan had never been anything but trainer and rubber, but Fleischer, though he was pro-Darcy from the moment he met him on the tug that brought him from the Cushing, has written - probably because of bad memory or unchecked research - many inaccurate things about Darcy, which have been accepted as fact.

Right. Now it's February 18. Around this time, Darcy was permitted a private spar with the huge Fred Fulton, who also trained at Goshen. The stories differ about the locale of the spar, the details not at all.

Fulton was no gymnasium trial horse. He was a noted knockout puncher and twice whipped Sam Langford. In 1918 he was considered the outstanding contender for Jess Willard's heavyweight crown, a match Rickard might have promoted if Dempsey, in his ferocious rampage towards the top, had not massacred Big Fred in the first round.

Although the Darcy "showing" was supposed to be over six rounds, it did not get that far. Fred Fulton was 14 stone, nearly 6ft 6in tall, with an 84½ inch reach. Darcy, then almost down to middleweight, 11 stone 6 pounds, stopped him in a round and a half.

Of the Fulton fight, Mick Hawkins later said: "Fulton had his left in his face all the time. I was surprised, so was Les. Then, in the second round,Les crossed him and knocked him clean out.

"There was a fella named McCarthy there, it might have been Luther McCarthy, and when Fulton came to, he accused McCarthy of pushing him into Darcy."

In view of Tex Rickard's previous prohibition on Darcy's actual ringwork being viewed, and his knowledge that the news of Fulton's destruction in so short a time was bound to leak out and scare off other managers with likely Darcy opponents, it looks as though Rickard already had sniffed that Governor Whitman had every intention of banning Darcy from boxing in his State. New York State was all Rickard was interested in - a bout at the Garden, and a million-dollar gate.

On March 3, Whitman banned Les Darcy. On March 9, Darcy and Mick and Grant Hugh Browne interviewed Whitman. Mick Hawkins said, "The Governor said: I'm sorry for you, boy, but there's a guy named Mclntosh who must have a big pull back in Australia. I just can't allow you to fight.' He seemed a straight shooter."

Whitman and Bat Masterson were also old buddies, though there may be no connection.

Whitman, in the newspapers, differed from Mick's "straight shooter" in the gubernatorial mansion. With all the peculiar savagery of the righteous, he attacked Darcy. "To permit him to box would be an offence against public decency. The people have backed me splendidly in this."

Many columnists, notably Marion T. Salazar, of San Francisco, protested at his vindictive tone, pointed out all the old truths, quoting Darcy's reiterated statement that he wanted only five fights and then he would enlist. They also reminded the Governor of "a more notable target, a young Briton in this land, who has not been banned." This would be England's Freddie Welsh.

By this time, Tex Rickard, regretfully, and in a friendly manner, had severed all connection with Les Darcy. Immediately, other promoters rushed in with offers of fights in other States. The storm of venomous abuse which filled newspapers was even more righteous and hysterical now that America was mobilising her first half-million men.

This flak often has a curiously Australian turn of phrase, as if written by O'Sullivan, or based on Australian articles of the same nature. This did not deter promoters who saw money in the now-notorious Darcy. The publicity was all grist to the mill.

On March 21, Darcy wrote to an Australian friend, "We are doing well and expect to fight Gunboat Smith on April 12."

A few days later, however, Darcy and Mick and Freddy Gilmore, his sparring partner, were on their way to New Orleans to discuss a proposed bout with old opponent Jeff Smith.

This was billed as "The first real middleweight championship contest since Stanley Ketchel beat Bill Papke July 5, 1909." It was a 20-round bout, and the promoter was Dominick Tortorich, manager of the Louisiana Auditorium.

On March 25, Governor Cox of Ohio announced he would bar Darcy from fighting in that Stale. In Milwaukee the three travellers conferred with Tom Andrews, a much-respected promoter, about his plans for Darcy's later meeting with either Al McCoy or Jack Dillon.

Here, the Boxing Commission refused permission. Atlanta made a bid for the boxer's services, but Governor Harris issued an indignant statement that Georgia would allow no such thing.

Passing through Chicago on April 5 - the day America entered the war -Darcy took the oath of allegiance and was given his first citizenship papers. He gave his age as 21, his occupation as blacksmith and professional athlete.

Both Tom Andrews and Fred Gilmore had recommended this step, and for once Darcy had taken good advice. In the photographs he looks fit, though rather thin. He had come down to middleweight limit rather fast. Old Mick looks fat and placid, every inch the keeper of a Galway pub.

Some say that the trio stopped off at Memphis in Tennessee to see Australian Mick King. Mick had likewise stowed away and left without a passport, but had had no publicity at all in the States, an occasional fight, and almost no abuse from Australia.

However, the Memphis sportsmen of our time agreed that Billy Haack of Memphis went to see Darcy train at New Orleans for the Jeff Smith fight. Aside from a persistent sore throat, Darcy was very fit.

On April 13, Governor J. Pleasant of Louisiana banned the match with Smith. The reason for his action, he mentioned, was the receipt of numerous appeals for cancellation from patriotic persons in his State. He added in his telegram to Tortorich, "Let Darcy follow noble example of Georges Carpentier before seeking athletic engagements in Louisiana."

It was now only five weeks since Darcy was originally banned by Whitman, which gives the lie to the trailing, depressed and melancholy, from Slate to State bit upon which all Darcy yarns feed with such vigour.

He must have been frustrated and infuriated at the injustice of it all, but he did not have his tail down. By environment and heredity, he belonged to a class which becomes, with each knockback, more obstinate and bull-headed. A similar person sat next to me in the aircraft in which we did the last lap to Memphis. He was going to get the Darcy story if it killed him.

In every city that the trio visited, O'Sullivan managed to get letters into the papers. For sheer vindictiveness and a baroque fury, they can scarcely be matched. They sound like those diabolical throat-cutting letters people wrote each other in the early nineteenth century.

For some reason, never fully explained, O'Sullivan always blamed Freddy Gilmore for "malign and wicked influences." As I have mentioned, we never had the luck to contact Gilmore, but 1 have read many of his letters, and he sounds like an average, decent, pleasant sort of fellow, always with an affectionate reference to "our dear old Les."

O'Sullivan never gave up. He had the same ironbound determination as Darcy, and the latter's death must have caused him severe deprivation.

Later he went to England and did not return to Australia until 1942. I quote him. Understandably, as public opinion had him firmly fixed in his role as party of the second part - "the tempter, the Judas," and so on - he was reluctant to speak to anyone about his role in the Darcy story, or indeed even admit his identity.

However, after our return to Australia D'Arcy Niland tracked him down, and there came the day when I jammed my ear against the wrong side of a phone receiver and heard him speak. After our American quest it was rather like hearing a ghost.

His voice was cracked and thin - he was then 73 - like a cranky cricket. However he civilly, if querulously, answered all D'Arcy's questions, which covered the entire history from the time O'Sullivan had travelled down from Brisbane in the train with Darcy and Mick Hawkins, and discussed ways and means of gelling out of Australia without a passport.

In almost every detail his story differed from Darcy's, even the fragments we had back-checked with five or six other people. He said only he knew the true story and he would never tell it, even though an American newspaper had offered him $100,000 to do so. He was protecting people.

His personality came across as that of the true Dublin jackeen; there was a supple credibility about it, even a kind of pulpy sweetness. He referred to Les as "that poor, misled boy," whom he didn't blame in the least for his ingratitude and cruelty.

After 10 minutes or so, D'Arcy incautiously mentioned that he had photocopies of many of the letters O'Sullivan had written to American newspapers in 1917, whereupon the old gentleman, not unnaturally, said, "get stuffed," and rang off.

In fairness, however, one should refer to a letter written by Mr O'Sullivan to the Sydney sports writer, W. G. Corbett, and dated a few days after Darcy's death. It is a lucid, well written letter, and highly believable.

He repeats that there was a contract drawn up between the two men on the Hattie Luckenbach, to the effect that he should get a third of Darcy's earnings for three years. This contract was lost.

Darcy then asked O'Sullivan to accept 25 per cent, which he did. O'Sullivan said that he had signed affidavits from several people that Darcy had called him his manager and had said he was paying him 25 per cent.

Fred Gilmore, said O'Sullivan, told Darcy he was crazy, said that he himself would act as his manager and would be satisfied with whatever Darcy paid him.

The major problem is that, in the American letters of O'Sullivan, various versions of the above appear, and also that no affidavits were ever shown. It is also hard to believe O'Sullivan, however valid his story may seem, after reading the fearful venom of his letters about Darcy.

One must give him the benefit of the doubt however, and admit that there may be some truth in his story and that less blame should be assigned to O'Sullivan than popular legend has decreed.

However one bends over backwards to be fair to E. T. O'Sullivan, it is difficult to be objective towards Billy Hughes and other politicians, who used their powerful friend Hugh D. Mclntosh's angry vendetta towards Les Darcy for their own ends. Snowy Baker, the dazzling, all-round athlete, may have been personally involved, or he may have been only Mclntosh's tool.

The whole question of conscription in Australia during the First World War forms a kind of complex infrastructure to the entire Darcy story, and no one of today has the right to judge the issue until he has studied what was written and done in those times.

Even in judging Prime Minister Hughes (and, like poor Father Coady when describing Hughes's ruthless sacrifice of young Australians, I freely confess, "I could minch him"), one has to understand Australia's unavoidably mimetic relationship with Great Britain - that just after a tiny Australian population had lost 28,000 of its sons killed and wounded in the idiotic Battle of the Somme, the British Army Council really could demand over 30,000 reinforcements immediately or it would disperse the Australian survivors of the AIF among British divisions.

Regarding Mclntosh's involvement, we can only say that his Sunday Times was virulently conscriptionist, that Stadiums Ltd had mercilessly thrashed every bout it could out of the boy Les Darcy as long as he was its own little moneybox, and then thrashed him personally when he broke with the firm.

We left Les Darcy in New Orleans, in mid April, having just been banned from boxing yet again. While in that lovely city he had met and larked around with the famous Memphis baseball team, the Chickasaw Tribesmen. National baseball star Waite Hoyt mentions him in his memoirs. "He got into a uniform and, man, did he give that ball a shellacking!"

Which does not sound as if Darcy were already sickening.

"I never saw such an ivory-encrusted grin," continues Hoyt. "He always had this big smile on. He didn't fire off about the Governor's ban, though Gilmore did. But you could tell he was humiliated about the slacker tag. What man wouldn't be?"

On April 19, Darcy and his friends travelled back to Memphis with "the Chicks." Les played his mouth organ, as usual. Mick Hawkins said he also played the violin, "but looking at those incredibly large hands, I couldn't believe it."

Mick King and Billy Haack met the train, and Billy said he had a scrap up his sleeve, Len Rowlands of Milwaukee, if he could get round Mayor Thomas C. Ashcroft. Following the example of his neighbour State governors, Tom Ashcroft had said Darcy could not box in his town. But Billy Haack winked. He knew Ashcroft well, and he had the gift of the gab.

Now, when D'Arcy Niland and I came into Memphis, it was late summer; there were cotton bales everywhere, even at the airport. The Wolf River, like a tangle of slate-blue wool, wiggled across the north of the city to join the huge Mississippi, very much like the Hawkesbury, with white-riffled mudbars and swampy beaches. There was the same fragrant openness which characterises the Hunter Valley. D'Arcy Niland said, "What a right place for the old Les to die in, it's just like home."

We found a taxi, and D'Arcy Niland gave the name of our hotel, the Claridge, pronounced "Clarge" in Tennessee. The elderly cabbie turned in open-mouthed astonishment and said, "I shorely have not heard a gentleman speak that way for fo'ty farve years, when I was stopped on Beale Street by a big country style fella in a derby, and asked the whereabouts of City Hall."

From further conversation, it was obvious that this long-before Australian was Mick Hawkins, Darcy's faithful "old horse." It was an endearing introduction to Memphis, where Darcy at last beat the boxing ban, was matched with a man he could have licked with one hand tied, and had sent his anxious mother in East Maitland a cable that the bad times were over at last.

"He was that pleased he did a step-dance," said Mick Hawkins.

We both loved Memphis. It was extraordinary how D'Arcy Niland became fit again, lost his leaden fatigue and turned into a dynamo. The climate was like that of Sydney at Easter, clear, bright, with a faint snap in the air. The landscape, the food, the big porridgy dawdling river, the many spires, we liked them all. Especially the people, as much like New Yorkers as Fijians are like Watusi.

It was a lucky place for us, as it was for Les Darcy. It seemed he had to die young, and I'm glad he died among the Memphis people, so warm, human, and kind. I'm sure they said, when his cortege left the town, "Y'all come back again, you heah?"

This Billy Haack, senior, was a beautiful little guy, built like a heavyweight and game as two red devils. He was born 1878, so he'd gone by the time we came, but we spent days and weeks with Billy Haack, junior, who was practically a replica of his pa.

Darcy's Billy could tell great jokes, had a squashed nose and a big smile. He'd give you the shirt off his back, but he'd take no sass from the pugs he managed. He'd take on a fighter as big as a house, and likely floor him.

We'd scarcely poured out our first cup of wonderful Southern coffee in the "Clarge" before Billy jr. was round to see us. Sure, he remembered Les Darcy, he'd been 11 at the time, and Les often came to the house and played baseball with him. He seemed to like kids.

"They picked on that boy, y'know," said Billy jr. "They wouldn't give him as much as a cornbread livin', and for why? Because there was things going on between the Australian Government and Washington, that's for why. And that O'Sullivan, a-tearin' at him for pure spite. It was enough to throw an angel off his perch."

"Did it throw Les?"

"Never. He looked like a big sunny tempered boy, but he was a man and had been for years. He knew why he was picked on when others were not. He was the one in the news, the champ, so he was the patsy.

"Pa thought the world of him, and Pa was a guy who got to know a man fast; specially a fighter. But Darcy was gentle, too gentle, that's why he never sued that mean old boy, O'Sullivan, or as much as said a harsh word about him. Pa would have knocked off his mean old head."

Billy Haack snr. took Darcy along to see Mayor Ashcroft, and Ashcroft, like most people, immediately took to the sincere personality of the boxer. Les said, "I don't think people here understand my true condition. I have 10 brothers and sisters and a mother and father at home. Until I began to make a success of fighting, they lived very humbly. I've seen too many men come back from the trenches unfit to earn a living for the rest of their lives.

"All I ask is that 1 am allowed to fight for my family before I go to the trenches. If I can place them in a position where they will want for nothing when I am gone, 1 will be satisfied."

He said that he was willing to enlist in the American forces at once on the condition that he be given leave of absence during June and July so that he might fight five times.

Ashcroft listened attentively. It was the first time since Whitman's rebuff that the Australian had been given a hearing by any State or City official.

Ashcroft then sent a telegram to Secretary of War Baker and Senator K. D. McKellar, junior spokesmen for Tennessee in the US Senate, strongly recommending that Darcy's request be granted.

He added, unconsciously repeating Australian newspaper statements of 1915 and 1916, that "Darcy as volunteer would mean great recruiting boom in every city he visits. Is anxious to do the best thing possible and I ask you to accept his offer."

That McKellar was a keen boxing enthusiast, and a friend of Ashcroft, may have swung the issue.

Darcy enlisted with the Signal Corps, aviation section. His examining officer was Captain Art Christie. Darcy passed all tests easily, and after physical examination was described as the most perfect specimen of manhood Christie had ever seen.

He was given the rank of sergeant in the reserve and, although he had actually enlisted unconditionally, he was given a fortnight's leave of absence to train for the Rowlands bout. He began this training on April 24.

I wish credence could be placed in Mick Hawkins's account of Les Darcy's last days. But in later years, when it was recorded, he had become forgetful and confused. He romanced a bit, too, tidying up the story according to his own sentimental imagination. I suppose he'd told the tale a thousand times in a thousand pubs.

No doubt about it, though, although he was only about 10 years older than Darcy, he loved him like a father. Les was always "my boy" to him, and Darcy's death just knocked the skids from under him. Until his death in 1958 at the age of 73, the O'Sullivans of the Lord Dudley in Paddington kept an eye on him, and he wasn't an unhappy man.

"He had a Shakespeare," said D'Arcy Niland. "That was his fame, and always will be."

What I give you here is the story told by Memphis men who were with Darcy during that last month, Winnie O'Sullivan, his sweetheart, who was with him when he died, and other people who vividly recalled what friends intimately acquainted with Darcy's last days had said.

Luke Kingsley, an astonishingly handsome old man, saw us many times. Aside from "knocking around the town" with Darcy, he had been a pallbearer at Darcy's funeral.

"Billy Haack fixed up accommodation for Les and Fred and Mick at the old Hotel Peabody (it's a store now) and training quarters at Dominick Zenone's. Dom had a gym behind his cafe-saloon, opposite the fairground entrance. The fairground had a track for roadwork.

"Les was some guy, you know.

"'Man, what a hand,' folk used to say when he shook hands. Coyle Shea said, 'Now, don't cripple me,' and poor Les was so careful with other folks' mitts it was funny.

"He was a priest type. I was a pro gambler and event announcer for Billy Haack's Phoenix Sporting Club, and although I am a Catholic - I'm still a nickel grabber at the church, matter of fact - I was nothing like Les.

"Les was a daily communicant at the church. Mick said he went to morning mass whenever he could, and always when he was in training. He was as straight as a yard-rule, a diamond. I tell you that from the bottom of my heart."

Another pallbearer, Coyle Shea, was still working on the News-Scimitar, where he'd been in 1917. "It was a fine, big smile that he had. Healthy, nice-looking hand with a congenial tone to his voice. You couldn't help liking him. He was just busting with excitement that he was to be allowed to fight at last, and also because his sweetheart. Miss O'Sullivan, had arrived in San Francisco."

Dominick Zenone's daughter said, "He had been as happy as could be while training. One of his front teeth ached a mite, but it didn't seem to bother him much.

"Ours was an Italian family, we sang and yelled a lot, and Les enjoyed it. He played my brother's fiddle. He played like a cow. Oh, you'd have liked him, I swear to you."

On April 27, his joints became stiff and painful and, because he was running a high fever, Billy Haack took him to St Joseph's Hospital and called the Phoenix Club's physician, Dr Bryce R. Fontaine, and also Dr J. R. Bigger, a dentist and friend of Haack's family. (Dr Bigger was alive in our time, but out of town, so we were not able to speak to him.)

Dr Bigger took alarm at the condition of a pivoted tooth - one of the famous two teeth which had been knocked off at the gums by Harold Hardwick in his fight with Darcy in February, 1916. Dr Fontaine didn't like the look of his throat, which was badly inflamed.

However, what was released to the papers was that the Australian was suffering from a slight case of la grippe ('flu) and would be fit for his bout with Len Rowlands, who, meantime, was vigorously training.

On April 30, Billy Haack asked for a week's postponement of the bout, which was agreed upon. Darcy was shifted to a pleasant private hospital, the Gartly-Ramsay. On May 2, Jack Read, one more young Australian boxer who was fighting in America without any fuss, visited Darcy and immediately wrote off to Sydney, saying that he looked terrible, was fearfully low and depressed and was dying of a broken heart. This impulsive letter possibly started the snowballing rumours in Australia.

Dr Bryce R. Fontaine, long retired and living in New York, later spoke to us. He remembered Darcy well. "No wonder he was a wonderful fighter. He not only had a wonderful constitution, but he had the greatest fighting spirit I've ever seen in a human being.

"Well, we got those tonsils out, and the teeth, and the pain and swelling in his joints diminished a tad.

"But dear Lord, strep! In those days! He was riddled with it. How he lasted a month is beyond belief, because in that time, of course, we didn't even have sulphur-based drugs.

"His joints were immovable, he lost weight rapidly, but he had the spirit of a lion. We gave him what antiseptic injections we could, but wherever the needle went in a big gathering appeared. He had bandages all over him.

"You know, he was conscious all the time, a man like that, with death tapping him on the shoulder, and he joshed the nurses. They loved him - the nuns at St Joseph's, and the girls at the Gartly-Ramsay. I never saw so many people cry when he died.

"It was all over in a flash, you know. One minute he seemed all right, the next he was dead. The strep was so diffused, his heart just snapped out.

"That beautiful young guy. The undertaker was reluctant to do the embalming, we had to take great precautions, that's such a mean bug."

When we later went to England, we gave three doctors the list of symptoms Les Darcy had shown from April 27. All three said at once: "Streptococcus, no mistake, run for the antibiotics!"

Up to the late 30s, streptococcus was a killer. From a seat of infection, the germ showered its poison into the bloodstream, and by lysing or dissolving everything in its way, swept aside the body's natural defensive barriers.

On May 20, the full information about Darcy's illness was released to the newspapers, and his condition described as critical. He received Extreme Unction, the last rites of the Catholic Church, from Father John Matthew Mogan, administrator of the Franciscan Hospital St Joseph's. In 1961 Father Mogan was long dead, but his friend and assistant, Monsignor Kearney, was still in Memphis.

Monsignor Merlin Kearney was bright and mischievous. "I once was young, very vivacious and innocent, and now I'm middle aged, very vivacious, and mean."

He remembered Darcy. Monsignor Mogan (as the young priest had become) had talked a lot about Darcy's tremendous fighting spirit. He was fighting mad when the papers all over the country began to say that Darcy had turned the game in and died of despair. He didn't think he was going to die. Darcy often spoke of his mother and father and the young 'uns, and said his position as a breadwinner, kept him going when things were rough.

Monsignor Mogan was once present when Darcy was delirious. Darcy thought he was in the ring, and several times he said, "The count is seven, but you'll never count ten on me." He also mentioned Jack Dillon. "The same thing is the matter with you, Jack Dillon," he said. "But we will both win."

All through these critical weeks, Gilmore, Hawkins, Mick King and Billy Haack snr took turns at his bedside. Towards the end, there was Winnie, as well. Darcy was never alone.

When we met Winnie O'Sullivan in Sydney, she was a woman of great dignity and stability, and it was easy to see in her face the roguish prettiness of the 19-year-old engaged to Les Darcy. "Mother said I was too young, and I mustn't have a ring until we could announce the engagement, so Les gave me a diamond bracelet instead."

Darcy had long been friends with Maurie O'Sullivan, Win's brother, who often acted as his second. Maurie eventually became New South Wales Minister for Health. The Lord Dudley, the Jersey Rd hotel owned by the O'Sullivans, became Darcy's Sydney home.

"Mother was very strict," said Winnie. "If she'd known I'd read Elinor Glyn she'd have had a blue fit. Les fitted into our family as if he'd been born into it. He was that sort of person.

"He'd go off singing and joking to the stadium to fight, and he'd say to my mother, 'Back in a few minutes, Mum!' When he came back, he'd serve in the bar - we had 11 o'clock closing then -or wash glasses. He didn't drink or smoke himself. He was very unselfconscious with people. He liked them, that was all that mattered."

As I type this, I can see D'Arcy Niland, sitting spellbound, soaking up every word. He was having a look through another person's eyes at the man for whom he had been named, and in search of whom he had trailed many weary and often perilous miles in America.

"He wasn't as much handsome as nice-looking and wholesome," she said, "but he had the most unusual grey eyes, a kind of dove grey. And that big grin!". How on earth, was this young daughter of a strict Irish Catholic family allowed to go to America? Her friend, Lily Molloy, the actress - "Australia's Mary Pickford" - and her aunt, Miss Vera Dwyer, were going to the States so that Lily could have a crack at Hollywood. Jack Molloy, a responsible brother, was going along to look after them. They begged Mr and Mrs O'Sullivan to allow Winnie to go as well.

"At first, they wouldn't hear of it. They relented. But they made me promise I wouldn't stay over there.

"We left Sydney March 17 on the Niagara and spent a week in Honolulu, then on one of the Great Northern ships to San Francisco, I got in touch with Les and he told me everything was going well, but not to come south until he had proved himself.

"At Los Angeles we rented a small flat, where we all stayed. There was a letter from Mick Hawkins saying Les had been operated on for tonsilitis, but he was fine. Still, I fretted, like any young girl.

"On Saturday evening, Lily and I went to confession, and when we came back we found Miss Dwyer and Jack Molloy in a terrible panic. There was a wire from Mick saying, 'Les is sinking fast in private hospital in Memphis. Please come at once.'

"Jack rang St Joseph's Hospital, which is where Mick had said he was for the tonsil operation, and found out he'd been moved. We rang the Gartly-Ramsay, but I don't think we got through. I was just paralysed with worry. Jack made the arrangements for me and Miss Dwyer to leave for Memphis the next night, Sunday. I suppose it was the 19th or 20th of May. It was a nightmare.

'That journey took nearly three days. We arrived late at night, booked into a hotel and went straight to the hospital. But I couldn't see him until the next day.

"When I went in, he said, 'Oh, Winnie, when they told me you were here I thought they were joking me.' He'd lost so much weight he just looked like a young boy. His arms were covered with bandages. He asked about everyone and then asked me to write to his mother. He said, 'Mum thinks I'm going to die, but I'm not.' Then he laughed."

Here I interjected, thinking of his premonition that he would die in the war. "Do you think he really felt like that?"

She said, "Of course he did. He died intestate. He would never have done that if he hadn't believed he was going to live. He just idolised his mother, and he knew she would never get the property unless he made a will leaving it expressly to her."

She continued: "That was May 23, and the doctors were delighted with the way he picked up. They thought there was a chance he might live. However, the next day, when Miss Dwyer and I went to see him, the ward sister said not to stay too long.

"It was unbelievable ... I said goodbye to him, and then ... I just reached the door of the ward when the sister called, 'Come quickly!'

"I ran back and put my arms around him, and he was dead. Mick Hawkins was crying like a baby; he wouldn't let go of Les's hand. I don't know what happened after that.

"The boxing man, Mr Haack, and his friends were wonderful. There wasn't any money, and they had to find out what the Darcy family wanted. The kindest people in the world, they were.

"That was May 24, a day or so later, the Saturday, I think, Miss Dwyer and I went to see about the Requiem Mass for Les, and Father Mogan walked us home. He was a little man with shiny glasses. He said he believed Les had never committed a sin in his life."

Here our quest ended. We had come to find out what we could about a live man.

The Memphis sportsmen formed themselves into a committee to handle the complicated task of embalming and the sending of the body back to Australia. Fred Gilmore and Mick Hawkins were useless with grief.

"Poor old Mick," said Luke Kinglsey, "he didn't know what to do with his hands."

"Pa was blowing his nose for days," said Billy Haack jr. "He had seen Les just 15 minutes before he died and asked how he was, and he said, 'Fine, Bill.' Pa said he was the gamest ever."

Not only Winnie, but others, told us of the rest of the story. How the action of the Memphis sportsmen sparked off an extraordinary public reaction, how people came to the train carrying the casket, and knelt down and prayed - the incredible scene in San Francisco, the greatest funeral ever given to a foreign sportsman.

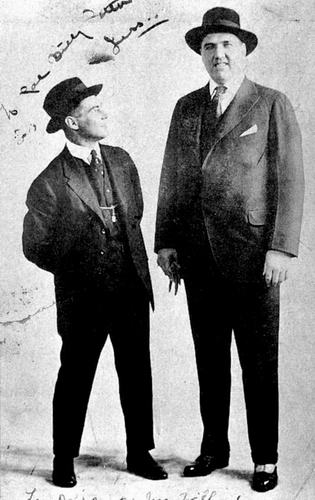

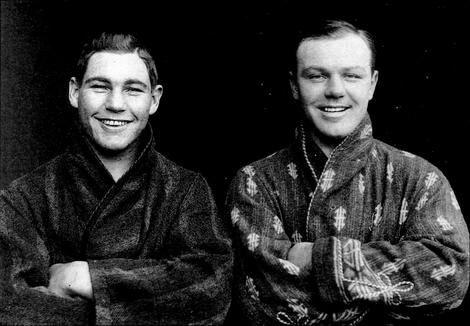

Les Darcy with Jack Willard, 1917

Les Darcy should not lie on the American conscience. Only a few hounded and abused him: the vain and stupid Whitman, the toadies who followed him, the would-be promoters who saw a goldmine eluding them, and struck back with vicious revenge.

America was at war. All at once, the ordinary people of the States saw this young man, struck down in the prime of his health and hope, as a paradigm of their own sons, perhaps also destined to die, homesick and puzzled, in a strange land.

"Such a waste, such a waste," said Jess Willard, the giant heavyweight champion, who had met Darcy and been amused at the young man's merry willingness to fight a man who dwarfed him.

The day before Darcy's body, in its magnificent metal casket, wrapped in both the Australian flag and the Stars and Stripes, was carried on to the Sonoma, Snowy Baker's usual boxing circular was received in America.

It had been sent long before Baker knew of Darcy's fatal illness, but in it Baker said that "the people of Australia thought the reason Darcy enlisted as an aviator was because of the long training required. By the time he was proficient, the war would be over and he wouldn't have to go."

Marion T. Salazar, the San Francisco columnist, said, "There are some things even the most heartless sportswriter must refuse to publish. This statement, from a man who made thousands upon thousands of dollars from Darcy, must be one of those things."

Though Baker, in a courageous gesture, asked for an inquiry to be made into his association with Darcy, and was acquitted of all wrongdoing, it is hard to erase from one's memory the brutally unjust words he said and published.